Belkis Ayón: the Princess Sikanekué

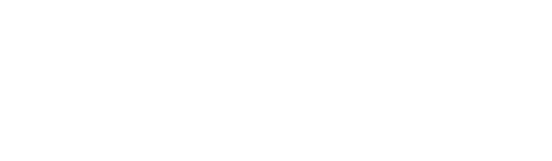

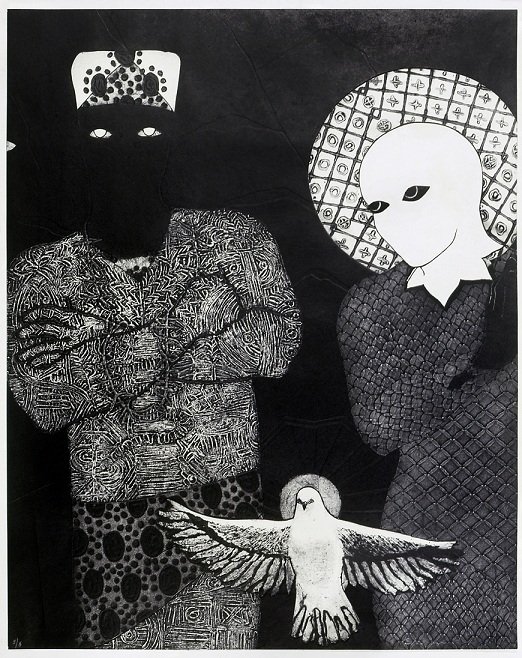

Belkis Ayón, La Cena (The Supper), 1991, Collograph

According to the Abakuá legend, “One afternoon the Princess Sikanekué went out to look for water in the river and accidentally caught the Tanze fish, in which the sacred spirit of Abasí lived. When Tanze felt trapped in the amphora that Sikán was carrying on his head, his roar was so enormous that the princess dropped the amphora in terror, causing his death. Because of this involuntary desecration, and to make amends to the river God, Sikán was sacrificed by her own father, and the skin from her back was used to make the head of a ceremonial drum (ékwe).”

This cruel legend is the founding myth of one of the most enigmatic, all-male, Afro-Cuban secret societies known as the Abakuá or black ñáñigos with its roots stemming from Ekpe and Ngbe secret societies of Southern Nigeria and Cameroon which arrived to Cuba via the slave trade. This secret society, often known as an Afro-Cuban version of Freemasonry, served as an inspiration for one of the most impressive contemporary artists, Cuban printmaker and, engraver, Belkis Ayón (1967-1999).

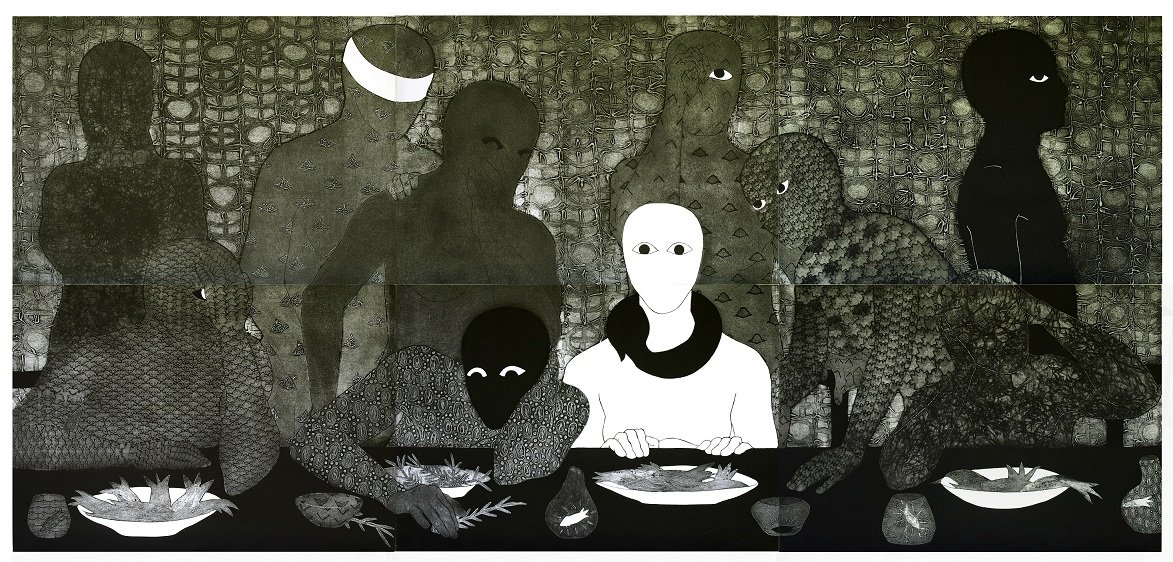

Belkis Ayón was considered a pioneer in the printmaking world and made a huge imprint on Cuban collagraphy (a labor-intensive printmaking technique that entails collaging materials onto a cardboard matrix, producing a variety of textures) and engraving, at a critical time when these print-making art styles faced possible diminishment amidst the Cuban Special Period and as Cuban Modernism took prominence. At only 18 years old, she began to investigate the secrets of the Abakuá society in-depth. As a non-believing, female observer, she studied the myths of the brotherhood through key books such as El monte by Lidia Cabrera and Los Ñañigos by Enrique Sosa.

Afro-Cuban Religion in Cuban Art

La Cena (The Supper), 1998, Collograph

Although much Cuban art depicts Afro-Cuban heritage through expressions of religious syncretism, Belkis Ayón's work is distinctive as her work goes beyond addressing race, identity, and myth. The color version of her work La Cena (The Supper, 1988), marked a “before and after period” for what would become 20th-century engraving in Cuba. La Cena shows the syncretization between Abakuá and Christian symbolism, as it depicts a version of the Christian “Last Supper,” replacing the central figure of Jesus with the princess Sikanekué. Eyes without a mouth, fish, snakes, roosters, and goats are all common images in her engravings, creating powerful and allegorical iconography.

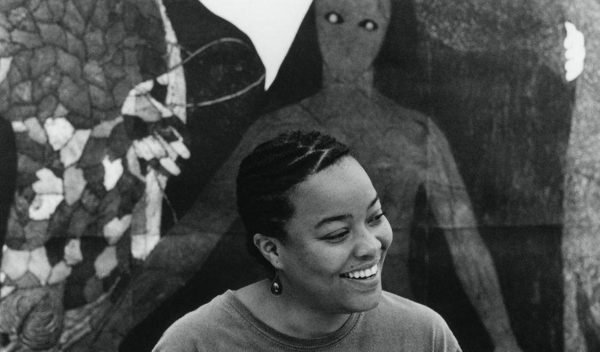

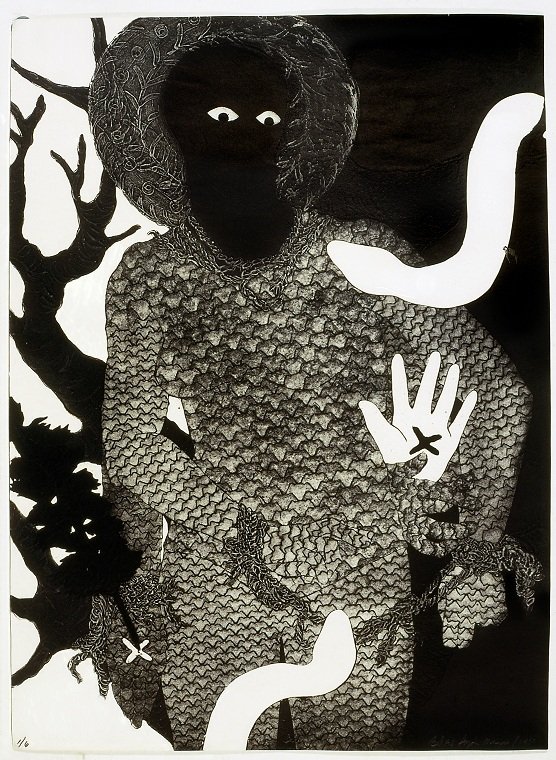

Belkis Ayón, Sikán, 1991, Collagraph

Through recognizing that many African religions rely on oral traditions, one may grasp what a challenge it must have been to create visual representations of gods, rituals, and myths that typically manifest through words.

At the time that she eliminated color from her work, Ayón also started to focus exclusively on Abakuá and Sikanekué, and her work took on a new level of complexity and power in her imagery. At this stage in her career, her compositions were marked by a variety of textures in austere tones that conveyed an otherworldly atmosphere. The mysterious, yet powerful force of her images conveyed stylized figures, with no facial features except wide, almost extra-terrestrial eyes.

Women in Belkis Ayón’s Iconography

Belkis Ayón, Untitled (Sikán con Chivo-Sikán with Goat) 1993, Collograph

Belkis Ayón’s work is not only known for its iconography of the Abakuá brotherhood but also for depicting androgynous figures to represent the silenced female in Abakuá society. Paradoxically, thanks to a woman, Ayón, the all-male Abakuá secret society reached universal recognition.

Some consider Ayón's work as a feminist representation; to which Ayón responded in a 1997 interview with La Gaceta de Cuba magazine:

"I have never thought of my work as feminist. I have never had such built-in vocation. The first person who attempted to draw attention to that aspect was the critic Eugenio Valdés, and perhaps there is some degree of truth that my work induces certain femininity, since it reflects my own existential uncertainty; but I have not conceptualized it like that. Sikán’s legend is a theme that I have been working within my prints since I was in San Alejandro and what has always called my attention is the female character’s status as a victim, but rather from a generic position, considering the connotations and the analogies that could be derived from such situation."

Belkis Ayón and International Acclaim

Together with artists Sandra Ramos and Abel Barroso, Belkis Ayón inaugurated La Huella Multiple (1996), a curatorial project that re-established the appreciation of Cuban collagraphy and engraving after its downturn during the decades that mark Cuban Modernism. Although these three Cuban artists have distinct styles, they are connected by a common theme – national identity.

Ayón's work includes an expansive personal collection along with at least fourteen collections displayed in museums and cultural centers around the world including in the National Museum of Fine Arts in Havana, Cuba; the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, U.S.; the Fort Lauderdale Museum in Florida, U.S.; the Museum of Latin American Art in California, U.S.; the State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia; the Van Reekum Museum in Apeldoorn, Holland; and the Ludwig Forum for International Art in Aachen, Germany.

Tragically, Ayón committed suicide the morning of September 11, 1999. Ayón’s legacy lives on through her notable impact on Cuban and international collagraphy and engraving. It is safe to say that without Ayón’s acclaimed, distinct style and highly-detailed iconography of the Abakuá, the Afro-Cuban secret society may have gone largely unknown to the world. More importantly, the world may have never known the immense talent and legacy of Belkis Ayón herself.