Cecilia Valdés and Slavery in Cuba

A bronze statue of Cecilia Valdés by Cuban artist Erig Rebull, commissioned by the City Historian, Eusebio Leal.

Unlike other Spanish-American countries, Cuba was the last colony to declare the abolition of slavery in 1886. According to UNESCO Habana, by that date, more than a million enslaved African men and women had arrived on the island. Colonial Cuba, from the foundation of the first villages in 1511 until the end of the 19th century, experienced and continues to experience, the consequences of a slave system from which both creoles and Spaniards benefited and in which the humanity of thousands of African slaves was stolen and abashed.

Cecilia Valdés or La Loma del Ángel is a costumbrista novel by Cirilo Villaverde published in 1879 that allows us to better understand the peculiarities and abhorrence of the slave society in Cuba. It’s considered the first work of this genre within Cuba and is representative of the abolitionist, nationalist, and independence ideals in Cuba.

One of the greatest values of the Cecilia Valdés novel is that it reflects the atrocities of slavery in Cuba at the hands of a mestizo writer of the early 19th century, with a historiographic precision and an anthropological value that brings the work closer to realism despite its romantic style. The descriptions and stories within the novel are unmatched in their understanding of the formation of Cuban national identity.

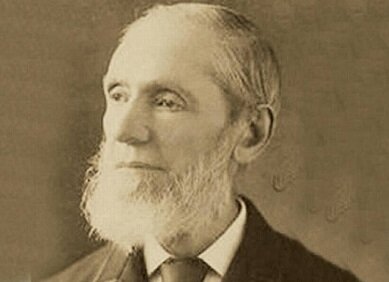

About the Author

Cirilo Villaverde

Cirilo Villaverde is known as the first Cuban novelist. At the start of his life, he lived in a mill where the slave system was in full force. His father was a doctor and was in charge of caring for Black slaves after being punished. From the humiliating and inhuman experiences he witnessed, Villaverde became a steadfast abolitionist. According to Villaverde’s testimony in Cecilia Valdés, he had to present a certificate of "cleansing of blood" to prove that he didn’t have Black ancestry during his studies in philosophy at the San Carlos Seminary. Due to his anti-colonialist inclination, Villaverde was imprisoned and exiled from the country like so many other Cubans throughout the island's history. From New York Villaverde finished writing the second volume and the corrections to his novel Cecilia Valdés. It's important to note that this novel was written in two parts. The first one was finished as a long story in 1839 when Villaverde was only 27 years old, and the second and last version was published in 1882 when the author had a greater intellectual and ideological maturity.

According to the Universidad de Guantánamo, while Villaverde was in New York in 1849, he also participated in the design of the current Cuban flag together with a group of patriots and allies who represented Cuban independence and annexationism. It isn’t surprising that Villaverde spoke out for the annexation of Cuba to the United States since at that time they embodied the ideals of progress, abolitionism, and individual freedom that many countries in Latin America and the world yearned for. In Cuba, the situation was very different back then.

The Context of the Novel

Cuban society in the 19th century had a hierarchical structure in which whites were at the top and Blacks were at the bottom. According to Villaverde’s description in Cecilia Valdés, there were several class divisions along the spectrum: “the captain general; the creole aristocracy possessing titles of nobility; the creole and peninsular [Spanish] plutocracy; the illustrated class made up of creole professionals, writers, and intellectuals; the peninsular popular class made up of small merchants, officials, and priests; and the creole popular class which included employees, teachers, artisans, peasants, and workers."

In the same way, Blacks were divided into three categories: “the mulattoes who were generally artisans; and free Blacks with a haphazard life that easily led to crime and slaves, the lowest and most mistreated category."

In the middle of that stratified and racist Cuba, Villaverde presents the story of Cecilia, a beautiful mestizo who aspires to be a part of the world of white aristocrats. Her goal is to marry Leonardo, a wealthy young landowner who would allow her to move up in social class. Leonardo's father, a white man who represents all the values of the conservative aristocracy in Cuba, opposes this union and arranges the engagement of his son to a white girl of his own class. Cecilia tries to stop the wedding with tragic results as (SPOILER ALERT) Leonardo is killed and the union is now impossible.

This romantic story of forbidden love was the author’s carefully crafted medium to show the readers of the time a critical portrait of the society in which they lived. A story of jealousy, incest, adultery, and racial and class prejudice appealed to the Cuban sensibility of the late 19th century but also interwove poignant symbolism around national identity.

The protagonist, Cecilia Valdés, is herself the representation of the humiliation of the black and mestizo race. She is the result of mulatto and white parents; her skin color makes her "look white." However, Cecilia is judged socially not by her "visible color" but by her "legal color." In an attempt to annihilate this new socio-racial class (that of mulattoes and mestizos), the concept of "purity of blood" was created and was something that allowed whites to maintain a superior status and condemn the natural practice of miscegenation.

Her last name, Valdés, was the one given to the children who were raised in the orphanages of the time, not because she was an orphan but because her real father, a rich landowner, didn’t want to give her his last name. In this way, the author represents the "colored" woman of the time as a fatal woman, the fruit of loveless sex, condemned to stagnation in a mischievous social class, courted by many men, embodying the archetype of the Caribbean eroticized and seductive woman amid a sexist, racist, violent, and backward society.

According to Figueroa Sanchez (2008), “The set of religious values that heroines usually possess — humility, simplicity, obedience, and kindness — are in no way the characteristics of Cecilia. On the contrary, she carries negative values, she is mulatto and not white, she is poor and uneducated, arrogant, ambitious, vain, envious, and cruel."

Cecilia is taught to deny her identity as a mulatto by her grandmother. She teaches her that there will be no space in society for her or her offspring until she can marry a white man. Following this trend, her grandmother denies her friendship with Nemesia, a young Black woman who, due to the dark color of her skin, was forbidden from any class ascent.

Various book covers for the novel.

The history of white supremacy is told by Villaverde by describing real places and daily activities where the social, political, and cultural hierarchies of the time were appreciated. The name of the novel mentions the Loma del Ángel, a place located in the heart of Old Havana where the old Angel Fairs were held every October 24. These festivities were part of the Catholic religion imposed on the colony that celebrated Saint Raphael.

In the description of the landscapes of the coffee plantation, "De La Luz," and the sugar mill, "La Tinaja," Villaverde exemplifies two places where slavery was typically practiced on a large scale in Cuba. In the first case, the owner, Isabel, treats her slaves maternally and humanely, to show the reader the possibility of peaceful coexistence with slaves without declaring an openly abolitionist position in the novel.

In the second case, the plantation owner is a ruthless and unscrupulous man who only sees objects of use and exchange in his slaves. His excess of power is exemplified in his treatment of slaves, especially Cecilia's mother, characterized by abuse, coercion, and hate to the point of driving her mad.

The machismo of the time is evident by women’s economic dependence on their husbands and the daily exploitation of Black slaves who were forced to have children that they didn’t want, breastfeed the children of others before their own, and endure all kinds of physical and psychological abuse.

But the novel also refers to the resistance of the Black community to the pressures of the ruling white class. While the whites celebrated at their dances and parties, the carriage drivers and men of color took the disused dances of the whites to create contra-dances as a gesture of cultural resistance.

Cecilia Valdés represents the synthesis of the African, the Spanish, and the aboriginal, and her lover, the young Leonardo, representing the apparent “white European purity.” A happy ending, expressed in the union of the couple, would have been the metaphor for the achievement of Cuban national unity, but the novel shows the impossibility of this love and therefore, of national reconciliation. Villaverde denies the corrupt Cuban society of the early 19th century while appearing to deny its salvation. However, he implicitly defends the need to build the ideal of a nation based on fraternity and unity between the “races.”

In the history of Cuba, as in this novel and much of the national literature, the figure of the free mulatto is the protagonist. They were fundamental in the defense of miscegenation on the island and the discovery of the creole, of the national conscience, and in the pro-independence wars. This romance is considered a foundational novel that served as a reference for other Cuban writers and intellectuals to create novels that explained the essence of Cuban identity. From the original work, there have been several interpretations created including zarzuelas, plays, and even films.

Bronze sculpture of Cecelia Valdés at the Plazuela del Angel in Old Havana.

Cecilia Valdés or La Loma del Ángel is taught nowadays in Cuban high schools as a resource to show young people the atrocities of the slave model and to recognize the cultural traces of that social-economic system. Despite having guaranteed equality to all members of society regardless of the color of their skin, Cuba continues to experience today traces of systematic racism as part of the indelible weight of four centuries of slavery. No doubt that the reading of this novel is tremendously educational and highlights the achievements of the social struggles over the last 60 years in Cuba while also showing much work that still needs to be done.